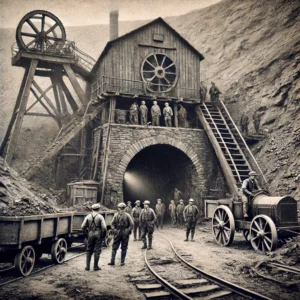

December 21, 1951, began like any other pre-Christmas day in the rural coal mining town of West Frankfort, Illinois. The atmosphere was filled with holiday cheer, especially among the night shift workers of the Orient Coal Mine, who were preparing to descend into the depths of the earth at 6:00 PM. Outside the mine entrance, a chalkboard displayed a festive message: “Merry Christmas to the Night Crew.” Little did they know, this would be their last shift before a well-deserved Christmas vacation.

The Explosion

At approximately 7:40 PM, as miners were busy with their tasks, disaster struck. Wilfred McDaniels, the night mine manager, was above ground reviewing shift records when he received alarming news: the power was off, and dust was billowing from the shafts. He quickly contacted John Foster, the mine superintendent, Arlie Cook, the mine manager, and the rescue crews. Meanwhile, Tommy Haley, a repairman working in one of the mine’s sections, relayed a dire message: “Something terrible has happened.” The 133 uninjured miners from the unaffected sections began their ascent to the surface.

Within moments, the town was in turmoil. An announcement at the local high school basketball game informed over 2,000 citizens of the explosion. Family members rushed to the site, anxiously awaiting news about their loved ones. As darkness fell, more than 218 rescue workers labored through the night, but those who escaped the blast had little hope that any of the trapped miners had survived. Tragically, as rescuers recovered bodies, the local junior high school gymnasium was repurposed as a temporary morgue.

The Sole Survivor

Amidst the despair, one man, Cecil Sanders, emerged as a beacon of hope. Trapped for a harrowing sixty hours in the mine, he endured extreme conditions that would have proven fatal for most. Despite having significant carbon monoxide in his lungs, Sanders survived, attributed to his acclimatization to the mining atmosphere. He was heralded as West Frankfort’s own Christmas miracle. By Christmas Eve, the death toll had risen to 119, and investigators began the arduous task of uncovering the cause of the explosion.

Investigations and Findings

Federal, state, and company inspectors worked diligently until December 27 to determine the explosion’s cause. Illinois Mines Director Walter Eadie concluded that the blast was undoubtedly triggered by methane gas. Prior federal inspections had criticized the mine’s methane control measures, but these recommendations were largely ignored. James Westfield, an official from the United States Bureau of Miners, labeled the disaster an “absolutely avoidable accident” resulting from negligence. Inspectors uncovered thirty-one violations of the Federal mine safety code, ranging from minor oversights to serious hazards that posed risks similar to those that had previously resulted in loss of life.

A Call for Change

The New Orient Coal Mine Disaster, alongside other significant incidents like the Cherry Mine Disaster and the Centralia Mine Disaster, garnered national attention, emphasizing the dire need for improved mining safety regulations. In response, on July 16, 1952, President Harry S. Truman signed the Federal Coal Mine Safety Act. This landmark legislation empowered mine inspectors to enforce compliance with safety provisions in any mine employing fifteen or more workers. The act granted inspectors the authority to shut down mines deemed dangerous and mandated better ventilation to control methane gas and dust accumulation.

The Federal Coal Mine Safety Act proved effective; since its enactment, only one other mining disaster occurred in southern Illinois. The lessons learned from the New Orient disaster helped reshape mining regulations, ultimately leading to safer conditions for coal laborers across the state.

The New Orient Coal Mine Disaster of 1951 is a significant chapter in the history of mining in Illinois. It serves as a reminder of the inherent dangers of the profession and the crucial need for stringent safety regulations. The tragedy not only claimed the lives of many but also prompted vital changes that would safeguard future generations of miners, ensuring that such a catastrophe would not be repeated.